There is no observable marketplace in the United Kingdom for transactions involving fractional interests in closely held companies, so valuing these interests is especially challenging, says Andrew Strickland. “The majority of the transactions which do take place are likely to be tainted” by one of the following:

- The transactions are between family members, and there is no certainty that arm’s-length pricing was applied; or

- The transactions are within a quasi-partnership relationship with a shareholders’ agreement or articles of association provision regarding the valuation basis to be applied.

For many years a corporate partner at Scrutton Bland in the UK, Strickland is now a consultant to the firm. He holds a FCA, which is a Fellow of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW), and is a member of the ICAEW valuation committee. He is also on the board of the International Institute of Business Valuers.

Strickland notes further challenges with valuing fractional interests: “Layered on top of these difficulties with the evidence base is the increasing recognition of the importance of discrete cash flows as central to the valuation mission. Majority cash flows are available to the majority holder; the minority shareholder may be excluded from some of these cash flows. It is therefore technically a firmer base to consider the differences between majority and minority cash flows and to undertake the valuation from those two different starting points. These arguments militate against discounting a whole firm valuation in order to derive a minority value,” he says.

And there is yet another complexity to consider: “An interest of 5% in a well ordered family company in which there are 40 other small shareholdings, none of whom are involved in the management, may be considered to be similar in many ways to a public company: if there is strong governance and no value leakage, both majority and minority holdings would be based on the same cash flows. The main valuation difference would be to reflect the reduced liquidity of the minority holding.”

Contrast this situation to “the hapless investor with a stake of 5% in a private company if there is a majority holder determined to squeeze out all of the perquisites of control for their own benefit. In such a circumstance there is both a governance deficit and value leakage, with the cash flows available to the minority being a world away from the control cash flows,” he comments.

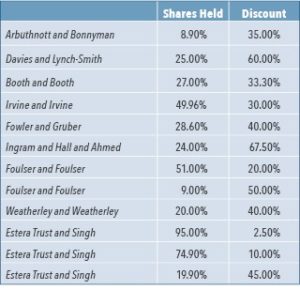

“Standard discounts for different sizes of shareholdings have to be treated with some very considerable caution,” Strickland advises. “We have to recognize that cases going through the courts leave a trail of evidence of the sorts of discounts which are considered to be appropriate to the circumstances of each case.” He offers a summary of discounts from a sample of relatively recent cases in the table below.

“Originally published in the August 2019 issue of Business Valuation Update (bvresources.com/bvu). Reprinted with permission.”